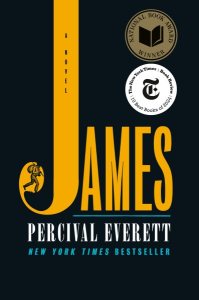

Since January 2014, the Whitney Book Bistro has selected a classic novel to start our new year. Most of the classics I have chosen would make a school recommended-reading list of white-Western literature. This is primarily because of the availability of multiple copies of the books, but also because they are comfort reads to get us through what might be a busy, complicated, and stressful holiday season. They are usually short and easy to read, but still serious, offering us important food for thought and social commentary. This year, we mixed that up by reading the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winning novel, James, by Percival Everett, a reimagining of Mark Twain’s classic, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, told through the eyes of the enslaved Jim.

Only one of us read the original story before tackling James. Our first responder reread both The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. She found the presentation of slavery in the original disturbing, which enabled her to appreciate Everett giving the power back to Jim. A few of us had unsuccessfully tried to read the original, with one member comparing her struggle to teens reading Shakespeare!

We moved around the table, with everyone having something to share or add. We didn’t seem to have as much back and forth as so often happens in the meetings. Our discussion showed both serious consideration and at times even awe, which I am not sure I can capture here. I expected more uncertainty and was prepared to show part of a video on code-switching, but everyone seemed to accept the use of standard English by all the slaves as necessary and as satire. I see now that the choice not only turned the tables on our expectations but also made the novel easier to read.

Our second responder remarked primarily on how violent and sad the story was, with a bit of incredulity at the revelation that Huck was Jim’s son. The next member to speak considered Sammy’s part to be the most profound. “She was dead when I found her . . . She’s just now died again, but this time she died free” (p. 225). Another member said that the death that struck him was the cost of a pencil; and someone else added that she will never look at a pencil the same again.

We talked a bit about the language and wanted to understand more about how Jim learned to read. Jim was a genius. One of us later commented that the whole point was not how he learned to read but that he could be educated. We were moved by the power of language in general, reading and writing in particular. Because of George’s torture and death, Jim was obligated not only to write his story but to write himself into the story; to free not just himself, but Sammy, Norman, his family, and others. Why did Huck need to be his son for Jim to save him? Perhaps that was for another reason: to subvert the idea that our black ancestry is only through the mothers? To emphasize that the bonds between enslaved and free are inherently unequal? Norman could have been saved, but he would not have been free. Huck was saved, but would he be free now, knowing he was black?

We overwhelmingly felt that people are horrible. How could people ever be so hateful? One of us read a poem that she wrote in 2021, “Nobody Can Be Nobody’s Property.” She also recalled her introduction to different cultural expectations when she met a Native American student who, as a sign of respect, wouldn’t look authority in the eyes. One of us shared experiences in the South, where the Civil War is called the War of Northern Aggression, where a black pastor said that slavery was bad, but some good things came of it, such as Christianity. She emphasized that nothing good comes from slavery – good things happen despite it. Which reminded me of the Slave Bible, in which select parts of the bible were removed, reducing hope for liberation and fortifying the system of slavery.[i] Slavemasters needed strong workers, but too strong was dangerous. They needed them capable, but not too smart. Things haven’t changed – we still feel the need to rule and control others.

In the end, what did we think of the novel? One of us was grossed out but tore through it. Another liked the first half but the second half felt too crowded with adventures. Still another made himself slow down to savor and understand. Others were overwhelmed by the cruelty, reinforcing what they already knew, but they kept reading. Usually, there is someone unable or unwilling to finish a book; everyone at the meeting and a couple of email responders, finished. Several people felt it was excellently written. Several agreed that they loved the parts when Jim was dreaming and had conversations with John Locke. Two of us listened to the audiobook and said it is well done.

One of us reread the book for our discussion and liked it better the second time. We barely even touched on the explosion of the riverboat as a metaphor for the systemic dangers of slavery. So many historical and philosophical references. Is James a story to be revisited? Will it stand alone?

What have you read that impacted you? What images and stories keep coming back to you? I overheard some discussion about how reading has declined[ii], which doesn’t seem a surprise given our digital culture of short videos and memes. Why does this, or doesn’t it, matter? So many books, so many ideas, so little time.

WORDS:

- Proleptic: anticipatory/foreshadowing

- “So, when we see him staggering around later acting the fool, will that be an example of proleptic irony or dramatic irony?” (p. 28)

- Trotline: A fishing line with multiple hooks that is used and reused.

OTHER WORKS DISCUSSED:

- “Amazing Grace” (1772) Hymn by John Newton

- Amazing Grace (2006) Film

- Finding Your Roots (2012+) Television with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

- The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) by Margaret Attwood

- Previous Book Club Selections:

- Puddin’head Wilson (1894) novel by Mark Twain

- The Vanishing Half (2020) by Britt Bennet

- The Water Dancer (2019) by Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Wench (2010) by Dolen Perkins-Valdez

[i] “The Slave Bible, as it would become known, is a missionary book. It was originally published in London in 1807 on behalf of the Society for the Conversion of Negro Slaves, an organization dedicated to improving the lives of enslaved Africans toiling in Britain’s lucrative Caribbean colonies. They used the Slave Bible to teach enslaved Africans how to read while at the same time introducing them to the Christian faith. Unlike other missionary Bibles, however, the Slave Bible contained only “select parts” of the biblical text. Its publishers deliberately removed portions of the biblical text, such as the exodus story, that could inspire hope for liberation. Instead, the publishers emphasized portions that justified and fortified the system of slavery that was so vital to the British Empire.” https://www.museumofthebible.org/exhibits/slave-bible

[ii] I looked up online whether reading has declined and the first hit is from a study mentioned a 40% decline from 2003 – 2023.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/aug/20/reading-for-pleasure-study